A Conversation on Kurdistan: With Harem Tahir and Diary Marif

Harem Tahir, an accomplished visual artist and Diary Marif, an award winning journalist, were reached out by PCHC MoM to be involved in a collaborative project together to discuss their respective careers, as well as their shared Kurdish identity. They are both from the Iraqi region of Kurdistan, a state that is not independent state and whose territory is divided among Türkiye, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. For decades Kurds have been fighting for self-determination, a struggle that continues today.

Early Life and Artistry

Following the Halabja massacre, a chemical attack launched by Saddam Hussein where about 5,000 civilians were killed, Harem and his family fled to Iran and spent several years in a refugee camp.

Because Harem fled Halabja when he was a child, he did not understand why he was living in a refugee camp. It was only when his parents explained to him the trauma they experienced, that he understood why he was far from home.

Harem Tahir, Looking Back.

From an early age, Harem turned to art as his main form of expression. What he could not communicate in words, he would capture in drawings, such as sketches of a tank, an aircraft or a bombing.

In the third grade, one of Harem’s teachers gave him a set of coloured pencils, noticing his artistic flair. After graduating from high school in Kurdistan, Harem went to college to develop his artistic skills.

Since then, art has become his method of portraying his life experiences, centering his Kurdish identity in his work.

“I try to show our resilience and the struggles we have endured. It is my way of sharing Kurdish stories with others,” Harem explains.

Early Life and Journalism

Diary was raised in a rural Bardabal of Iraqi Kurdistan. He recalls a lack of quality in necessities - power, clean water, and healthcare. He also saw a lot of corruption, war, and brutality under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, and then under Kurdish leadership after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. He hoped for democracy and freedom for his people, but corruption and nepotism weakened Kurdish institutions, leaving ordinary people struggling with unemployment and unpaid salaries.

Diary’s first steps into becoming a journalist were writing about the Iraq war, including the corruption, injustice, and brutality of the Kurdish parties. He also noticed the absence of media coverage about rural Kurdish areas which gave him a sense of responsibility to write about Kurdish issues and advocate for other marginalized minorities.

“I joined with a group of journalists who encouraged me to start writing,” Diary says. “That is how my career in journalism began. I am still continuing that path today.”

Being a Kurd in Canada

Harem and Diary both immigrated to Canada in 2017, noticing the stark difference in rights, safety and stability compared to minorities in the Middle East. They now had greater freedom to express their art and stories. However, like a lot of immigrants, Harem and Diary felt homesick, missing their relatives and the sense of community from the Kurdish people. Harem describes cultural identity as living between two worlds, where Canada provides stability, and Kurdistan is where his roots are.

Harem Tahir, Seeking Safety.

“I am grateful that Canada gives me safety and the freedom to create what I want. Meanwhile, Kurdistan will always stay with me. Kurdistan is where my family and memories are. Every chance I have, I would like to visit back and spend time with them.”

Diary adds:

“I love Canada’s diversity. I have met people from many diverse backgrounds, whom I have shared Kurdish stories. But I miss the strong social fabric in Kurdistan. In Kurdistan, if someone has a problem, families and neighbours help immediately. That does not exist in the same way here.”

Kurdish Oppression

Kurds from Türkiye, Iran, Iraq, and Syria have distinct issues, but freedom and recognition of their identity is a shared struggle.

Throughout history, Kurdish identity has been suppressed, such as the Kurdish language, their symbols or claiming their identity.

Diary with his colleague Sherwan Sherwani

Journalists are prone to imprisonment for reporting on Kurdish issues. Even Kurds in the diaspora could put their family back home at risk for being vocal about their adversities.

Diary recalls one his colleagues, Sherwan Sherwani, who was imprisoned for exposing the Kurdish leadership’s corruption. “He has been imprisoned since 2020. The Kurdish leadership accused him of spying, but they arrested him because he challenged their power.”

The challenges extend abroad, as Kurds are often pressured to deny their identity when introducing themselves, since Kurdistan is not an independent state. There is also a lack of support for Kurdish artists, as they have no funding and cannot make a living from their art.

Harem talks about the adversities Kurdish artists face abroad and how he uses art to express his lack of freedom:

“There are almost no official institutions, art councils, or galleries that display Kurdish art internationally. Freedom is never complete for us, but art remains my way of expressing it. It allows me to turn my search for freedom into something visible and shareable, even within constraints.”

Representation

Growing up Kurdish, Harem and Diary have an intrinsic understanding of displacement, genocide, and having their stories be neglected by mainstream media. Diary points out how in Syria, Kurdish people have an army that has fought not only for Kurds but for other minorities as well.

In Harem and Diary’s case, they use their artistry and journalism to authentically capture the stories of marginalized people - whether it is Palestinians, Ukrainians, Baluchis or Africans.

Diary talks about the methodology he uses to document the stories of marginalized groups:

“As someone who has gone through those difficulties myself, the first thing I do is listen. I pay attention because I care about their stories. Since 2019, I have worked to cover minorities in Canada because they often have no other platform. My goal is to give them a voice because I see myself in them.”

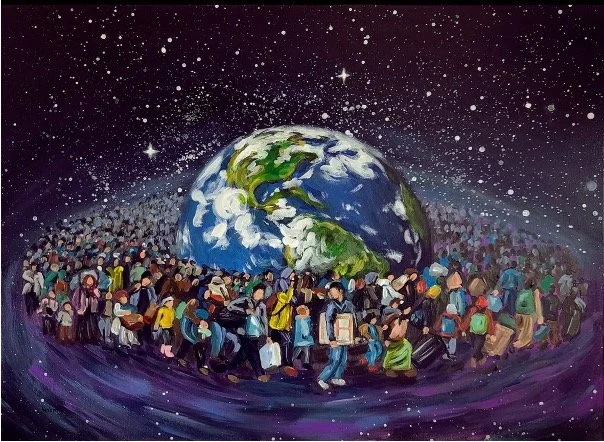

For Harem, the audience is the most important part of art. The first paintings he did were of Halabja after the 1988 chemical attack to express the pain his community felt. However, as he grew with his artistry, his work expanded beyond Kurdish issues. Wherever he saw people suffering, he felt compelled to respond through art.

“Art is universal. It is not limited by religion, ethnicity, or borders,” Harem describes.

“I am Kurdish, but my art is for anyone facing hardship. My goal is to give a voice to people who do not have one, whether they are from Kurdistan or from somewhere else in the world.

Beauty in the culture

Despite oppression and hardship, there is beauty and knowledge to be shared through one’s identity. Unfortunately, international media has failed to show the richness of Kurdish culture; thus, Harem and Diary understand how dire Kurdish representation is. They do not want their people viewed just as fighters; they want the people of Kurdistan to be seen as human beings with a culture, traditions, art, and literature. Diary talks about the mainstream media’s complicity in Kurdish oppression and what is needed for Kurds to be viewed beyond their struggles:

“International media relies on information from state media in Türkiye, Iran, Iraq, or Syria - all governments with a history of suppressing Kurdish voices. What we need is independent investigation, real journalism that tells the truth of Kurdish life - both the struggles and the achievements.”

Harem hopes to portray the humanity of Kurds through his art. Their stories, resilience, and most importantly remind the world that they exist.

“I want international media to show more than just war and conflict,” Harem says. “Kurds have a rich culture - music, dance, cinema, literature, strong women leaders, and even Nobel Prize winners. Too often, the Kurdish story is reduced to violence and resistance. I want the media to show our cultural and human side as well.”

Ultimately, Harem and Diary’s stories are about resilience and keeping their culture alive through their artistry and journalism. Their life experiences influenced how they navigate their work and ensure that Kurds have a voice. When asked about the future of Kurdistan, they are hopeful, despite all the challenges their people have historically faced. The new generation of Kurds is more connected, critical, aware, and vocal about their issues than ever before, and with access to technology, they can be louder about their stories.

“I saw this during recent Newroz celebrations,” Harem recalls. “Decades ago, celebrating Kurdish New Year was dangerous. But now, because of social media, Kurds from Iran, Türkiye, Iraq, and Syria came together in ways that were not possible before. This gives me hope that our voices will keep growing stronger, and that Kurdish people will continue to play a significant role in the region’s future.”

Diary adds:

“After the death of Jina Amini in Iran, for example, Kurds and other minorities came together with a new energy and determination. We have been fighting for a century, and the younger generation gives me confidence that change will come. We are moving closer to achieving recognition and, most importantly, freedom.

Annotation and Works Cited

Marif, Diary. Kurdish refugee artist paints 'stories that need to be told'. 12 May 2025. 28 August 2025.